The Sacred History of Pretzels

The Plant-Based Origins of Everyone's Favorite Snack

This is the last article in my series The Food History of Easter and Passover—Through a Plant-Based Lens, where I explore the symbols, stories, and rituals of these holidays through the food traditions that have evolved around them. I hope you’ve enjoyed it. I would be so grateful if you would hit the ❤️ at the top or bottom of this post, share, and comment. It lets me know you’re there and helps other people find Compassion in Action!

How the Church Shaped Diets in Medieval Europe

Pretzels—those deliciously pillowy-soft or satisfyingly crunchy and salty treats—have a long and unexpected history tied to Lent, the Christian season of fasting and reflection before Easter.

As I’ve shared in past articles as part of this series on Easter and Passover food traditions, Lent was traditionally a time when Christians abstained from all animal products for 40 days. These fasting practices have largely been forgotten in modern times, replaced with an emphasis on animal-based foods that were once the very things avoided. But history tells a different story.

In medieval Europe, the Christian church shaped every aspect of daily life—including food. People, especially peasants, followed both the natural seasons as well as the liturgical calendar, which included several periods of fasting and abstinence:

Lent: The most significant fasting season, lasting 40 days before Easter. People abstained from meat, dairy, and eggs.

Advent: A fasting period before Christmas, less strict than Lent but still involved avoiding rich or animal-based foods.

Ember Days: Quarterly days of fasting and prayer that marked the changing of the seasons.

Other Observances: Feast days, vigils, and saints' days often had their own dietary restrictions.

Practices varied by region and denomination, but the message was clear: for much of the year, animal products were not on the table. In other words, for centuries, abstaining from animal products was the tradition not the exception.

The Pretzel in Manuscripts and Monasteries

One food that has lost its connection to religious tradition is the pretzel.

Legend has it that pretzels date back to around 610 CE. A monk in Northern Italy or Southern France is said to have rewarded children for learning their prayers with little twisted pieces of leftover dough. These "pretiola" (Latin for "little rewards") resembled folded arms in prayer. (Imagine someone praying with their arms crossed over their chest — each hand touching the opposite shoulder.) The three holes in a pretzel were said to represent the Holy Trinity.

While that origin story is debated (beware of neat little historical legends!), what we do know is this: the word "pretzel" likely comes from the Old German brezitella, derived from the Latin bracchiatus, meaning "arm" (in reference to its shape).

By design, pretzels were egg- and dairy-free, making them ideal for Lent, since Christians were expected to abstain from all animal products (meat, eggs, milk, butter, and cheese) during this time. This wasn’t a fringe idea; it was a widespread religious practice that shaped everyday meals for centuries.

Pretzels, made simply from flour, water, salt, and yeast, fit perfectly within those dietary rules. They provided sustenance, symbolism, and even a little comfort—without breaking the rules of the fast.

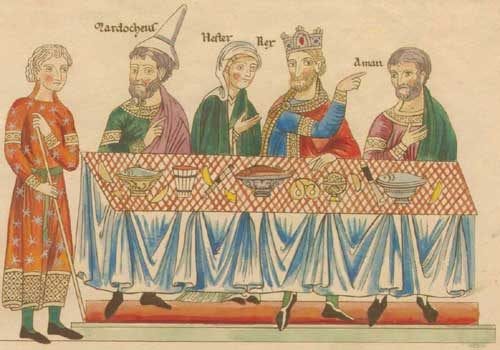

Monks distributed them to the poor as both sustenance and a religious symbol. In fact, pretzels became so popular they were even featured in religious manuscripts and artwork.

One of the most remarkable examples is the Hortus Deliciarum ("Garden of Delights"), a 12th-century encyclopedia created by Herrad of Landsberg, an abbess at Hohenburg Abbey in Alsace. This manuscript, the first known encyclopedia compiled by a woman, includes a scene showing a pretzel—possibly the first known depiction of one—as part of a grand medieval feast.

Can you find the pretzel in the image below?

Pretzels and Heroism in Vienna

Fast forward to the 16th century: During the Siege of Vienna in 1529, as the Ottoman Empire attempted to capture the city, legend has it that monks working in a basement bakery—making pretzels—heard strange noises beneath them. Realizing that enemy soldiers were tunneling under the city walls to stage a surprise attack, they alerted the authorities in time to thwart the invasion. As a reward, the Austrian emperor gave the pretzel bakers their own coat of arms, which includes lions holding a pretzel, and the pretzel became a symbol not only of faith and sustenance but also of vigilance and resistance.

As charming as this story is, it is most likely apocryphal. But even if it’s more legend than fact, it speaks to the long-standing connection between pretzels and Vienna, where they remain a beloved part of the city's culinary and cultural identity.

From Bavaria to Bars: The Pretzel’s American Journey

Pretzels were introduced to America by German immigrants, particularly those later known as the Pennsylvania Dutch, in the 17th and 18th centuries. While soft pretzels were prevalent initially, the first commercial pretzel bakery in the United States, producing what some believe to be the first true hard pretzels, was established by Julius Sturgis in Lititz, Pennsylvania, in 1861. By the late 1800s, pretzels had become a cheap, salty snack served in bars and saloons — their saltiness conveniently encouraging more beer consumption.

Over time, the image of a pretzel paired with a stein of beer came to symbolize Gemütlichkeit — that uniquely German sense of warmth, friendliness, and cozy cheer often associated with gatherings, comfort food, and good company.

Today, pretzels remain a beloved staple of German culinary tradition, whether twisted by hand at bakeries or served with mustard at beer halls. And best of all? They’re (typically) accidentally vegan — a simple combination of flour, water, salt, and yeast.

And yes...you can absolutely make your own. Check out my recipe for Homemade Soft Pretzels.

I also created a page where all of the articles and recipes in this series lives: The Food History of Easter and Passover—Through a Plant-Based Lens. Thanks for reading!

In this series:

The Meatless History of Lent: The tradition of abstaining from animal products during the 40 days before Easter

Homemade Soft Pretzels: Delicious and historical!

Tempura: The Plant-Based Origins of Japan's Favorite Fried Dish: What Lent, Language, and Latin Have to Do with Tempura

Carnival: A Meat-Free Tradition: the surprising origin of the word and its historic connection to meat

Celebrating Easter without Eggs: What better way to celebrate these ideals than by choosing objects that don’t just represent life and hope—but truly embody them?

How a Plant-Based Seder Celebrates the True Meaning of Passover: By centering our meals on foods that give life rather than take life, we align our behavior with the values we hold.

Enjoy my Passover and Easter recipes anytime.